The Roots of Modern Yoga

How did an ascetic approach to renouncing the world become a globalised industry focused on postures? In this course we explore the development of modern forms of yoga, from traditional texts to contemporary practices. In the process, we highlight trends – as well as influential teachers – that have shaped this evolution.

Although some of what is taught today has ancient roots, other components – such as sequences of postures – emerged more recently. When, where, and why did these changes occur? Priorities shifted in the early twentieth century, with the promotion of physical methods for health and wellbeing. This inspired new systems of practice based on āsana, which were aimed at urban householders.

Most earlier yoga was a full-time commitment pursued by renouncers. Its methods were less focused on posture and more concerned with subtle techniques of transformation. Some of these are still widely taught, but they get less attention than bodily contortions.

The structure of the course is outlined below. It was prepared by Daniel Simpson, author of The Truth of Yoga: A Comprehensive Guide to Yoga’s History, Texts, Philosophy and Practices.

Start Date: 18 January 2026

Course Duration: Seven Weeks

160 pages

On-Demand Video

The main video component of your course. On-demand means you can watch at the time that suits you.

6hr 52min

Community Discussions

These free Zoom sessions are not part of your main course materials. They are led by OCHS-affiliated scholars and open to students enrolled in any course.

Explore other areas of Hindu studies! Meet tutors and students from other courses!

Monday, 26 January, 12noon

Tuesday, 3 February, 2pm

Thursday, 12 February, 3pm

Saturday, 21 February, 5pm

Sunday, 1 March, 6pm

These are all UK times. Recordings are available for any sessions you miss

Roots of Modern Yoga

Session One: Ascetic Beginnings

In the earliest descriptions of yoga, the body was an obstacle to spiritual freedom. Its desires kept people entangled in cycles of suffering, seeking gratification from worldly activity. The simplest response was to disengage, restraining the mind and the senses to focus within. The only reference to posture was a stable seat for meditation. Some practitioners also engaged in harsh austerities, such as standing on one leg for years on end – embracing discomfort to help them detach.

“The yogi never neglects or mortifies the body or the mind, but cherishes both. To him the body is not an impediment to his spiritual liberation nor is it the cause of its fall, but is an instrument of attainment.”

B.K.S. Iyengar, Light on Yoga

Session Two: Reappraising the Body

The first non-seated postures were arm balances, which were effectively warm-ups for subtler methods. They appeared in texts a thousand years ago, as the influence of Tantra inspired haṭha-yoga. Instead of mortifying the body, practitioners transformed it. Working with the breath, and new techniques known as mudrā, they used physical practice to raise vital energy up the spine, dissolving the mind. Over the centuries, haṭha-yoga became more dynamic, including a wider range of postures.

“Go into your own room and get the Upanishads out of your own Self. You are the greatest book that ever was or ever will be, the infinite depository of all that is.“

Swami Vivekananda to American students (1895)

Session Three: Philosophical Hybrids

Modern yoga often blurs the distinctions between different worldviews. Teachers say yoga means union and comes from Patañjali, combining ideas that contradict each other. The Yoga Sūtra is based on the dualist philosophy of Sāṃkhya. However, most explanations use non-dual ideas from Vedānta and Tantra. This began a long time ago, but the nineteenth-century influence of Vivekananda and Western esotericists was significant, blending Indian teachings with some of the theories that shaped New Age thinking.

Session Four: Disguised Innovation

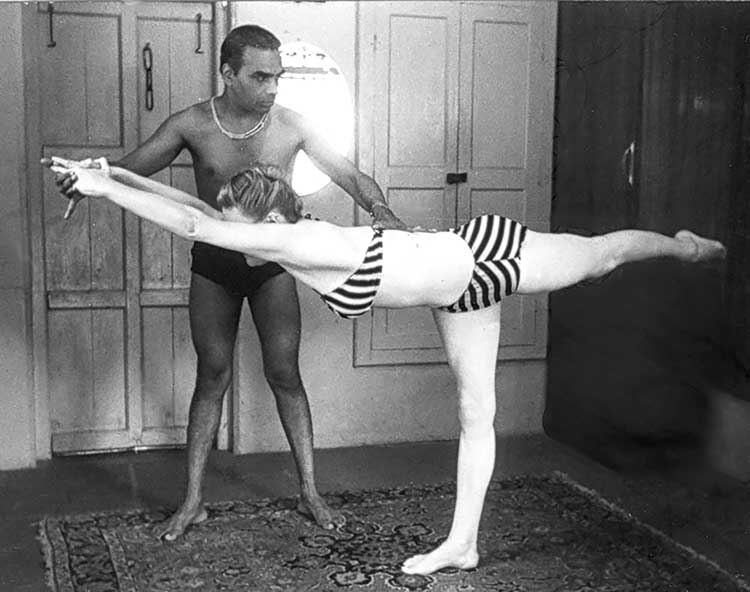

Many common postures – including warriors and triangles – first appear in texts in the twentieth century. Sun salutations may not be much older. Yet both are now foundations of the popular style known as vinyāsa flow. It is difficult to say where they came from, not least since teachers imply they are timeless, but there are parallels with systems of gymnastics taught in India. Boundaries blurred between yoga and exercise as they were widely combined. Perhaps the most influential innovator was T. Krishnamacharya, who taught – among many others – B.K.S. Iyengar and K. Pattabhi Jois.

Session Five: Science and Wellness

Yoga is often presented as therapy, healing anything from back pain to trauma. Its links to Indian medicine date back centuries, but the emphasis on health and wellness is more recent. In the early twentieth century, teachers of yoga sought to prove its effectiveness by scientific means. Two in particular shaped this process – Kuvalayananda and Yogendra, who had the same guru. They adapted his treatments for the general public, prescribing āsana, prāṇāyāma, and purifying kriyās. They also framed yoga in the language of progress, which others have embraced with technological metaphors.

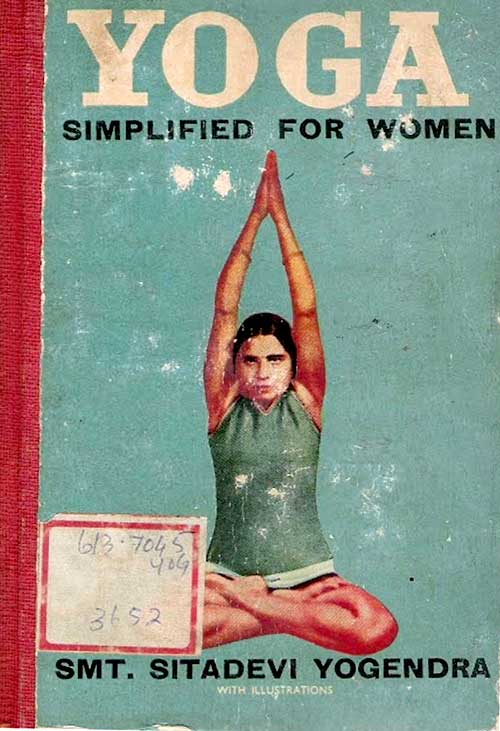

Session Six: Female Practitioners

Session Six: Female Practitioners

Most traditional texts were composed by men and describe male ascetics. However, teachers and students today are primarily female. What accounts for this shift? The influence of women on the history of yoga is significant – particularly in cultural exchanges between East and West. Indian teachers borrowed ideas from female traditions of “harmonic gymnastics”, whose practitioners shaped the development of similar systems such as pilates and somatics. Some scholars even argue that the average modern yoga class owes more to Western women than to medieval texts on haṭha-yoga.

Session Seven: Politics and Business

Debates about the ownership of yoga and misappropriation are now widespread. Commercialisation is rampant all over the world, while politicians have taken advantage of yoga’s popularity. In 2014, India’s prime minister won United Nations backing for an International Day of Yoga, held each year on June 21. Yet this event has sparked a backlash, due to connections with Hindu nationalism. This session reflects on tensions in modern yoga – particularly the quest for authenticity. As practices change, what keeps them anchored in tradition? Not everything is yoga because someone says it is.

Everyone who finishes the course will receive a certificate for 12 hours of study.Teachers registered with Yoga Alliance can log these as continuing education with a YACEP.

Associated Courses

Your Tutor

Daniel Simpson

Daniel has a Master’s degree in Traditions of Yoga and Meditation from SOAS, University of London. He’s also a devoted practitioner of asana, pranayama and meditation, which he’s studied on numerous visits to India since the 1990s. Daniel previously worked as a foreign correspondent, which helps him make complex subjects feel accessible. He writes about yoga for magazines and on his website: www.danielsimpson.info